Waste management in Jordan and Lebanon, a buried fortune.

By: Zain Jbeili, and Hazm Almazouni.

Waste management in Jordan and Lebanon, a buried fortune

Poor waste management and lack of implementation of necessary plans in both Lebanon and Jordan have caused billions of dollars from recyclables to be lost.

“I always collect recyclable materials and sort them into packets,” said Nermina Alrifai, a Jordanian Integrated Co-Teaching (ICT) teacher.

In a Facebook post, Alrifai tried asking her friends about broken electronics recyclers in Amman but did not receive any answer. “I was looking for options to help recycle old electronics to organize a field trip for my students as part of the school environmental awareness program,” Alrifai explained.

In Jordan, there are unfortunately few initiatives aiming at raising awareness about the environment, in general, and recycling, in particular.

Free flow of materials goes to waste

Our research found that waste management is poorly developed in low-income Jordan and Lebanon, because of insufficient funding, poor operational waste management, weak legislative provisions, and a lack of awareness regarding collecting and disposing of garbage in an environmentally friendly and cost-efficient manner.

A 2018 World Bank study dubbed What a Waste 2.0, and the UNDP’s Solid Waste Value Chain Analysis, show that Jordanian citizens generate an average of 0.81 kg of waste per day.

This means that Jordan generated about 28 million tons of municipal waste over the last decade -without considering the 1.2 million Syrian refugees in the country- and in 2021 generated three million tons. This amount is expected to climb to 5.2 million tones.

About 48% of Jordan’s waste is landfilled, 45% is openly dumped, and only less than tenth (7%) is recycled.

Most recycling is done by waste pickers with no operational facilities in place. Pickers and scavengers usually sell what they collect to intermediary traders, who, in turn, sell recyclables to local factories or have them exported after sorting and proper packaging.

Based on the Jordanian recyclables trading market prices, we estimated that at least $1 billion worth of recyclables has been buried or dumped over the last decade.

We, however, believe that the real value of the waste is considerably higher.

Because of the lack of data on scrap metals composition, we considered all scrap metals to be tin, ignoring aluminum and copper prices, which are noticeably higher.

We also did not take into consideration the value of compost potential biogas produced from organic waste, knowing that Alghabawi landfill project—the only operated one to gather the biogas from waste out of 18 in Jordan — would reduce the financial burden on Amman Municipality by saving about five million dinars ($7 million) of electricity bill annually.

Ahmed AlJarah, a Jordanian recyclable intermediate trader said that “taxes for exporting recyclable cardboard are so high, and the only existing factory in Jordan can’t take all the locally collected materials.”

He believes that the government should come up with a special legislative package for this business, taking into consideration the benefits of all parties involved.

“This would achieve stability that is needed for the market to thrive,” he added.

Municipal waste also contains organic products. According to the most recent WWF report titled Driven to Waste, about 2.5 billion tons of food go uneaten worldwide each year.

If food goes to the landfill and rots, it produces methane, which contributes as much as a tenth of our global greenhouse gas emissions.

As for Jordan, waste contribution to gas emissions almost doubled from 7% in 2010 to 12% in 2016.

Ahmad Obeidat, the spokesperson for the Jordanian Ministry of Environment, told us that Jordan’s loss from landfilling amounts to billions of dollars, and that the country is now looking at waste from a different perspective.

“Trash is now seen as a blessing instead of a curse,” he said.

Obeidat added: fully supported by the Jordanian king, two years ago, Jordan began to deal with the environment in a new and advanced way, by launching Framework Law No. 16/2020.

According to Obeidat, a quarter (26%) of the consumed electricity in Jordan now is solar energy, and there are future plans to develop the waste management sector in partnership with the international community, international organizations and private sector.

Lebanon and the garbage crisis

Every Lebanese citizen generates 0.93 kg of waste a day on average. In 2021, Lebanon produced about 2.4 million tons, and over 23 million tons in the last decade, without considering the 1.5 million Syrian refugees.

The Lebanese government has been struggling to manage the country’s waste. The situation aggravated in the summer of 2015 when the government failed to reach an agreement on the disposal of trash. Garbage piled up in Beirut’s streets, making the capital look like an open large landfill, and prompting angry protests, a civil society movement emerged, calling itself “You Stink.”

Despite the authorities’ attempts to suppress “You Stink,” the movement captured wide public support in Beirut but lost momentum later in 2015.

Under government direction later on, piles of garbage were collected under bridges and in empty fields. The basic issue, however, remained unsolved, namely an agreement on a long-term solution that did not pose a threat to public health.

It was not until the spring of 2016 that the trash disposal arrangements were in place.

According to Lebanon’s second biennial climate change update report to the UN from October 2017, in most cases, the solution is open dumping and open burning domestic waste. Around 670 open dumpsites have been reported in 2010, three quarters of which (504) are municipal waste dumpsites, and the rest are construction and demolition dumpsites, and industrial solid waste is still dumped with municipal waste, since no industrial waste treatment facilities exist in the country.

Burning money

In 2013, however, Lebanon managed to recycle less than fifth (17%) of all generated waste, burying or openly dumping recyclable materials worth approximately one billion and 50 million dollars over the last decade.

The country also reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by almost a third, from 11%, about 137 Gg (thousand tons) in 2010 to 7% about 100 Gg (thousand tons) in 2013, simply by flaring a significant part of the methane coming from green waste fermentation at open landfills.

The other unburned methane successfully made its way into the atmosphere, and none of it was used to generate electricity that the country desperately needs during the ongoing electricity crisis.

Salim Khalifa, the head of Lebanese Beam of the Environment association that runs a waste sorting plant since 2015, an activist and a member of Lebanon Eco Movement has direct daily contact with waste management and waste recycling issues in Lebanon.

Khalifa believes we misinterpret the waste management process.

He said “landfills are for nonrecyclable waste, such as construction waste. Domestic waste should be fully recycled”

Although the Lebanese People’s Assembly approved the waste management bill in August 2018 and the waste sorting at source bill in 2019, Khalifa does not think that the problem is only a legislative one.

He especially emphasized on the necessity of modernizing the operations part of waste management, he added; “to help Lebanese citizens abide by the waste sourcing law at source, the municipalities have to secure a full infrastructure for such process”

“It’s not acceptable to collect the domestically sorted waste with old waste pressing trucks that mix it back. The point is to deliver the sorted waste to the sorting plants so they can shred and pack it properly, turning it to source material,” he said.

Rich countries are looking away

To understand where rich countries stand with waste management in middle and low-income Arab countries, our team analyzed the International Development Statistics data which clearly shows that internationally, the attention to waste management in the region isn’t up to the mark.

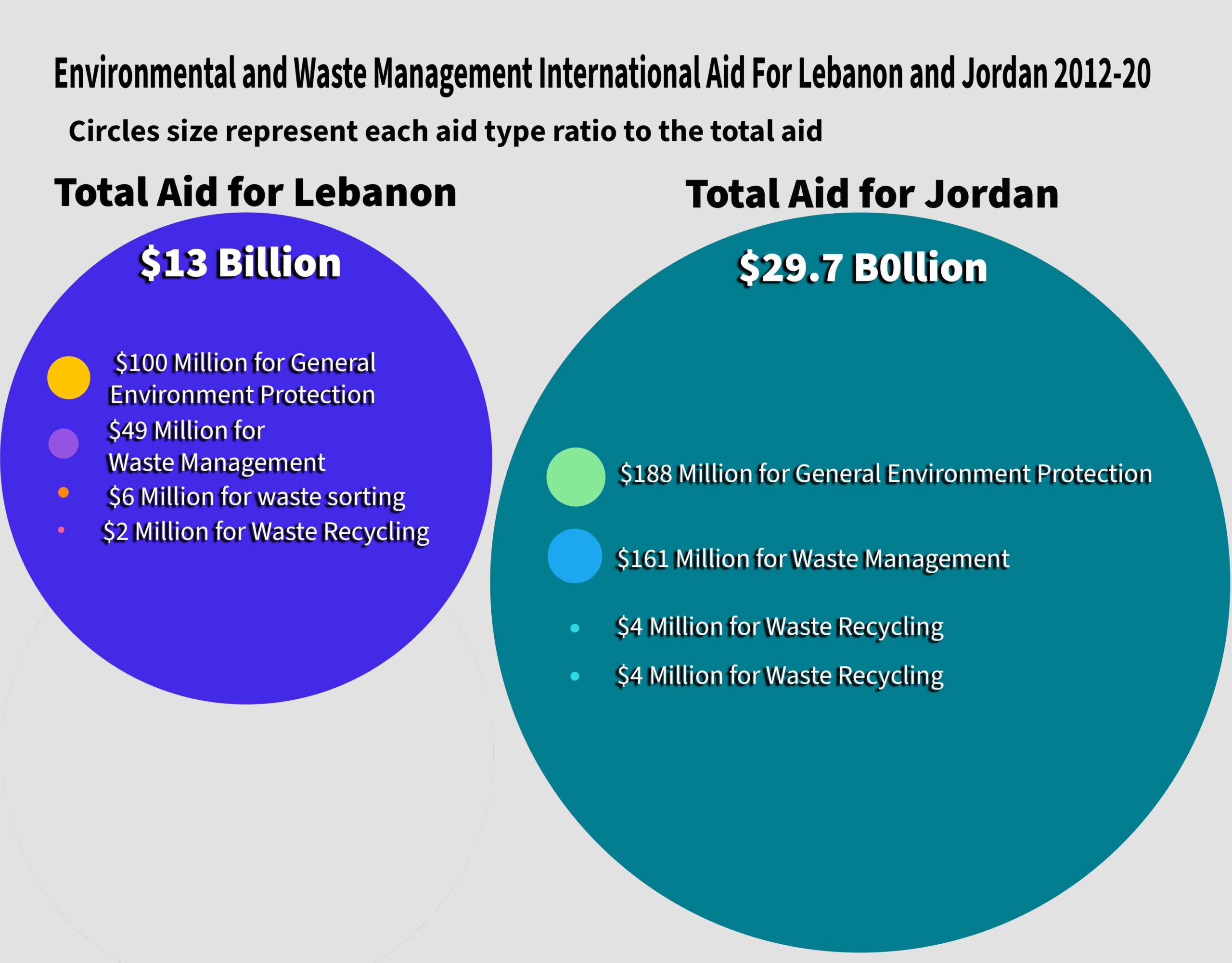

Between 2010 and 2020, Jordan received $29.7 billion in aid; only $1 out of each $200 of it was targeting waste management. During that same period Lebanon received about $13 billion in aid, $1 out of each $270 it was for waste management.

With great confidence, we can also say that rich countries are not interested in helping these countries sort and recycle their waste. Given that out of each $10000 of overall aid, Jordan received in aid only $1 for waste sorting and $1 for recycling, while Lebanon got $5 for sorting and $1.6 for recycling.

It may make sense here to ask: Why should developed rich countries help low and middle-income countries in dealing with their environmental issues?

Ali Darwish, the head of the seventh branch of the Syndicate of Lebanese Engineers answered that question for us during the conference entitled (Environmental Reality and Climate Justice in Lebanon: Towards COP 27) on Friday, October 14, 2022.

Darwish said: “Environmental justice and the principle of Common but differentiated responsibility have not been achieved so far since 1992, and the major industrial countries responsible for the most carbon emissions and climate changes still refuse to assume their responsibilities”.

Darwish added: “at the Copenhagen Conference, rich countries pledged $100 billion annually to poor countries to help them adapt to climate change. Despite that, we are more than a decade ahead. The goal has never been met, and the total amount of climate finance provided by developed countries by 2019 was $79.6 billion”

The Lebanese Minister of Environment, Nasser Yassin, spoke about the three most important reasons for Lebanon’s inability to fulfill its obligations towards the environment.

First, crises such as the economic and social crisis are pressing on everyone’s agenda, forcing officials to manage daily immediate crises, and delay thinking about the expected problems coming with climate change at the expense of the future ones.

Second, international cooperation and the international community failed to reach the levels of this major issue, such as climate change. The major industrialized countries are still remiss in dealing with these global issues and assuming their responsibilities. They generate most of the global emissions since the Industrial Revolution, and we small countries are now bearing the burden of the carbon emissions, and these countries are still evading their pledges to finance developing countries and poor countries to confront the climate crisis.

The third reason is that the environmental dialogue is still elitist and has not yet reached the ordinary citizen. Environmental dialogue is still using technical expressions that do not reach people and are unable to create a broad public opinion about this issue that has a profound impact on their lives and their future.

Yassin added: “Environment investment is not a luxury, it’s an opportunity. According to our study. Every $1 investment in green economic recovery plans returns $2.3 of profit, and Lebanon should benefit from such opportunities”

The world today has lost its first environmental battle in preventing a two-degree rise in global temperature because of the lack of commitment by all nations to the goal of carbon neutrality, according to Engineer Salim Khalifa, one founder of the Lebanese environmental movement and the national coordinator of the Arab Network for Environmental Development (Raed).

Khalifa says: “that in this political chaos, the absence of the state, mismanagement, and the absence of good governance and social justice in Lebanon, everyone has turned into consumers of the environment. In such crises, the environment has turned into a weak team and the media refuses to defend it”.

Regulations are not enough

In Jordan and Lebanon, environmental legislation exists. Lebanon, a bit ahead in this direction, has already passed a law on sorting waste at the source while Jordan doesn’t.

But almost unanimously speakers and experts from Jordan and at the aforementioned conference agreed that passing the law is the first step towards good waste management, and environment protection.

The great challenge lies in the application of these laws on the ground, and an important part of this challenge is the cooperation of people in the application, and the creation of an infrastructure that helps citizens to implement environmental instructions.

In Jordan, these laws need to be enforced on the ground, according to the recommendations of the Economic and Social Council in its recent Arabic version report for 2020 about the environment.

For example, the General Framework Law for Waste Management having existed since 2006, the Jordanian Ministry of Environment announced its seriousness in implementing its provisions regarding the indiscriminate disposal of waste around mid-2021.

In its report, the Jordanian Economic Council attributes the inability of the Ministry of Environment to enforce environmental laws to the ministry’s political weakness and the government’s poor environmental strategy.

The Council concluded with the need to improve the political weight of the Ministry of Environment by improving its financing, providing it with human and technical resources, strengthening its regulatory and supervisory role, and supporting its independence. Also,the concept that environmental protection does not take place separately, but rather within the framework of sustainable development, considering the reduction of poverty and unemployment, must be reinforced.

The former Jordanian minister of environment for 2005-09 and the minister of energy for 2009-10 Khaled Irani told us that “the ministry of environment does not have the required political weight in almost all developing countries as the same as in Jordan”.

Mr. Irani said: “It is essential to enforce the Ministry of the Environment because its work intersects with all other ministries and institutions implementing the development agenda in any country”.

Mr. Irani believes that waste management has to be trusted to the private sector, which considers the waste as a source of profit, while the government and public institutions keep being legislative and monitoring institutions of the process.

Recycling is certainly beneficial. According to many studies, recycling metals for manufacturing can save three quarters of the energy needed to manufacture them the traditional way by mining.

Multiple published studies confirmed that using recycled steel reduces air pollution by over three quarters (86%), water use by two-fifths (40%), and water pollution by three quarters (76%).

And using aluminum scrap, CO2 emissions can be reduced almost nine times (92%) compared to raw aluminum, and saves 95% of the energy needed for primary production.

And finally, by reusing copper scrap, we reduce CO2 emissions by over two-thirds 65%.

Waste management is a long-standing project. ZDF Studios in its documentary followed the birth of the recycling industry in Berlin that has built one of the most innovative and effective systems in the world. Turned out that Hitler’s Nazi regime developed the amazing success as a raw material supply source for the military industry. Which tells us that our waste is a fortune that can’t be simply buried.